Little Italy

Due to several family discussions, this story of family memories will be revised and expanded. Stand by for further additions.

Around 1900, Sam (Salvatore), age 5, and Tony (Antonino) LoPresto, age 3, came to America with their mother and father, Maria and Ignazio. Ignazio was a Merchant Marine who had obtained passage on a ship bound for Brownsville Texas. From there they traveled to Streeter Ill. and lived there, in a boarding house. Maria worked in the boarding house baking and cleaning. Ignazio worked at a bottle works company and also the railroad. The couple quickly earned enough money to take a mortgage out on their own Brownstone home. It was just a block from where they had been living. Ignazio continued to work his same two jobs. He may have also jump on a merchant ship. Maria started taking in boarders of her own. She charged for room and the evening meal. She baked bread in a brick oven on the outside of the house. The story goes that on a good day she could sell 50 loaves. She sold her bread at 4:00 am for 1 cent while the going rate was 2 cents. She also sold cheese and salamis for men’s lunches. She also took in laundry and mended clothing. Sam would go to the bottle works and earn money doing small labor jobs and running errands. He learned to speak English well but never went to school.

Soon the little family had earned enough to sell the brownstone at a profit and still had enough to return to San Biagio, Sicily to buy additional property for an olive grove and farm. Sam later told his grandchildren, “I was an American boy. I never wanted to go back”. His parents told him if he worked very hard and planted the olive grove he could return to America on his own. It took him two years to complete the planting. Sam returned to Streeter and the original German Family boarding house around 1911. He worked at the same factory and railroad as he and his father had.

About a year later, Sam's younger brother Tony came to America. The day he arrived in Streeter he started work at the railroad. Sam wrapped up railroad spikes in handkerchiefs and put them in Tony’s pockets. At that time you were hired by weight not age. It worked! The two brothers were on their way.

By 1911 unskilled labor to work on the railroad was needed. Sam and Tony ended up in Hillsdale in the first wave of Italian immigrants to settle here. Several of the families originated in San Biagio Sicily. Sam was instrumental in sponsoring some of the young men and their families into America. Families wanted to know someone, if possible, who could help translate and find them work. Sam and Tony did both. Family names that followed are familiar to Hillsdale residents. The Rossettis, the Spiteris, the Brunos, the DeFrancos, the Savarinos, and many more joined the ranks of Italian immigrants. They quickly becameproud citizens of the United States.

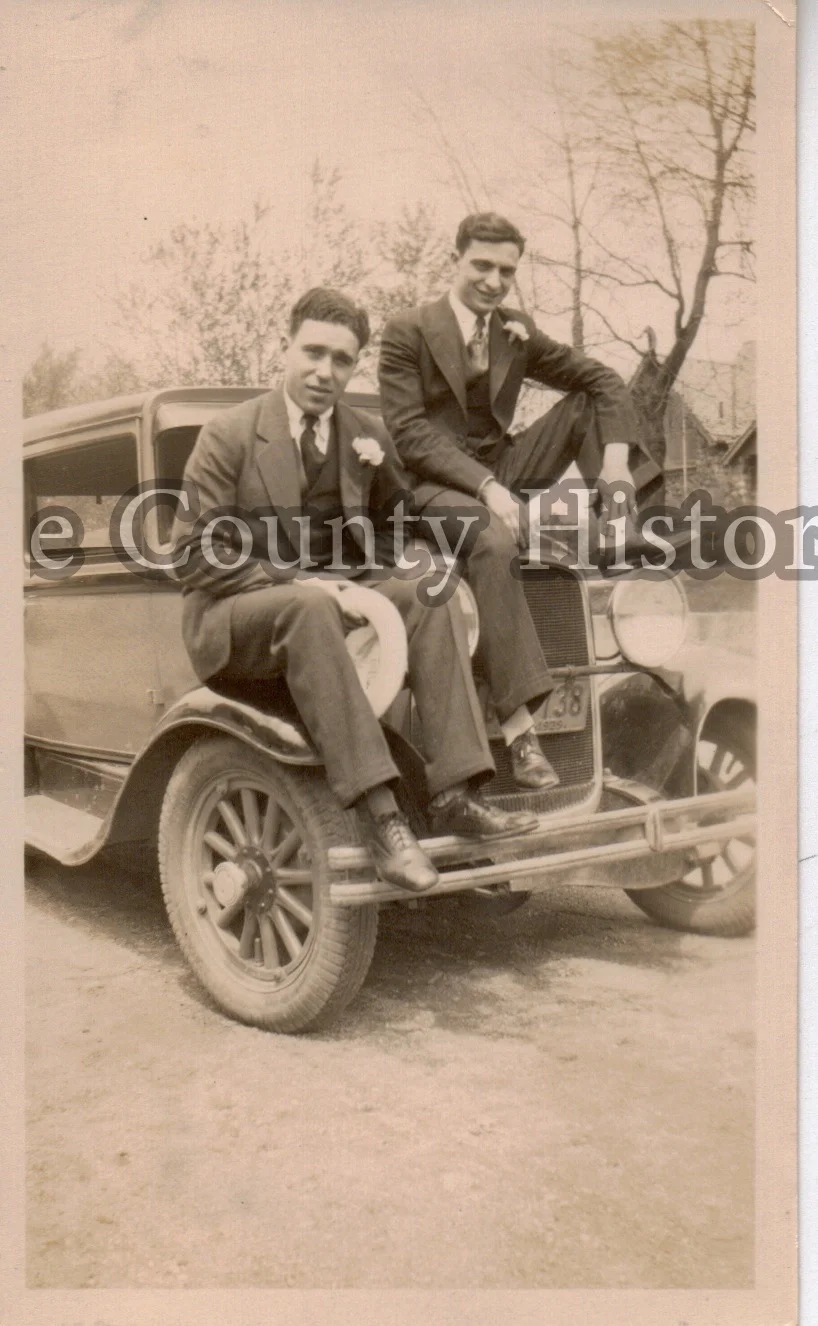

Tony, Jennie and Sam LoPresto

Sam married Jennie (Vinzcenginna) LoPresto in 1916. She was 16 years old and was also from San Biagio. She and her sister and two brothers had moved to Chicago with their parents. She worked in a dress factory making shirtwaist dresses. She didn’t like the Idea of moving to the ”country” but gave in knowing that she could take the train to Chicago any time she wanted.

Various LoPresto, Spiteri and Savarino daughters

The LoPrestos made their home in what came to be known as Little Italy, an area that included parts of St. Joe and E. South Street, as well as Griswold Street across from the Trinity Lutheran Church. The Italians weren't the majority of homeowners in that part of town, but their exuberant love of life, intense work ethic and strong family values set them apart.

Grandchildren of the three brothers

When weather halted railroad construction Sam and Tony worked for the Toledo Ice and Coal Company, which took ice from Baw Beese Lake in the winter to store for use later. Sam worked for the Alamo Manufacturing Company, located in Little Italy, before establishing his own gravel andlandscape business. His brother Tony, owner of the gravel business, was almost buried alive when a truck dumped itscontents over him. Tony never worked there again. Sam took over the business and his affinity to grow and create natural Landscapes thrived. His mark was made on the city of Hillsdale as it grew, being responsible for the seawall at Sandy Beach, the landscaping of Stock Field, Stock’s park, parts of the Arboretum, and the President's home at the college. The Hillsdale Community Health Center and the design of the St. Anthony's cemetery wall were all Sam's handiwork. Both Sam and Tony worked at the Alamo, railroad, Toledo Ice Company and unloaded and loaded flour on train cars at Stock’s Mill. Neither of the brothers ever worked just one job at any given time.

The first business of their own was a fruit and vegetable cart drawn by a horse. The LoPresto Fruit and Vegetable Wagon eventually sold ice cream to children with sore throats and then to others who enjoyed this cold treat. Sam briefly owned a bar next door to his family home at 44 west St. Joe. Ginny made him close it down after fighting and a KKK cross burning on the front lawn occurred. The building was renovated and turned into an apartment building.

By 1923 the Brothers added a storefront to their home at 40 West St. Joe St. and sold fruits, vegetables and an assortment of ice cream, milk and candies. From this small specialty store emerged the LoPresto Grocery. Tony LoPresto operated the store instead of that gravel pit. Sam’s children helped in the store as it flourished.

The Depression shut down factories and business alike. Banks failed and the brothers lost much, as did others, but Sam and Tony helped to "carry" the families of Hillsdale’s south east end (Italian or not) who had no money to pay for food.

Men from Little Italy play cards in the back yard

In the early 1950s Sam moved the portion of his home that had housed the grocery to his property near Oak Haven. There it was used by the myriad of family members who came from Chicago for long visits or just family who wanted to stay at the lake for a few weeks in the summer. Friday night fish fries were often set out on long clothed tables covered with salads, watermelon, fish, spaghetti, homemade bread and sausage, olive oiled green beans, corn on the cob, cakes, pies and those old round galvanized steel basins filled with sodas and ice. Life was good for that second generation of Sicilian grandchildren.

The closeness of the LoPrestos was echoed not only within Little Italy families, but also across the Italian community. Games of bocce ball and cards regularly brought the men and boys together. Holidays and Holy Days were excuses for parties, great food, music and dancing. The Fourth of July was celebrated with great exuberance. Sam was instrumental in the bikes parades, penny tosses, and famous chicken chases. He even had a tent restaurant at the celebration and at the fair. These hard working families found time to laugh and enjoy life.

Joe Savarino, with the clarinet.

On most days children could identify the aromas from the different kitchens to decide where they would stop for a snack. If a mother was ill, the other women in the neighborhood would swoop in to care for her home and children until she was on her feet again. This unequivocal support helped dilute the sting of names the children were sometimes called in school. Even the hate rhetoric of the Ku Klux Klan when they came to Hillsdale in 1923 failed to subdue the spirits of the families in Little Italy.

Peter Savarino with his cousin.

The only drawback with such a close community was that the acquisition of English in the older members was inhibited. Their children became the translators. Camilla Spiteri, at age six fluent in both Italian and English, helped not only her own parents, but also the other women in Little Italy with grocery shopping and, after she'd grown up a bit, banking. In 1913 Camilla's parents, John and Rosaria, came to America from San Biagio, Sicily in steerage class. Camilla was only 11 months old. John had a job in the mines in Pennsylvania that he'd gotten through Italian friends already working there. After three weeks he moved his family to Hillsdale, where other friends were working on the railroad.

With the workers separated into different ethnic groups, John found himself with other Italian men, led by one of their own who spoke at least rudimentary English. It was a solution that effectively eliminated the confusion generated when men who spoke different languages worked together. John moved to the Alamo Manufacturing Company, where he remained for 25 years, doing the same job as different companies bought and used the building. Eventually he opened a shoe store with his sons.

Camilla Spiteri Savarino with Aunt Lucy from Cleveland.

Camilla married Peter Savarino, another resident of San Biagio, Sicily. In 1913, when he was five years old, Peter came to America in steerage class with his parents Joseph and Rosalia. Joseph worked in the coal mines of Pennsylvania, but when Rosalia died in 1919 he was unable to continue to care for his children. He put them in an orphanage, a situation Peter didn't tolerate for long. He ran away from the orphanage, but stayed nearby to keep an eye on his little brothers Frank and Sam. On his own at age 11, he worked first in the mines and then shining shoes. Convinced he could do better financially, Peter presented himself at a factory. With impressive self-confidence he delivered a convincing patter that persuaded the factory manager that he was a tool and die man. Nothing was further from the truth, but by the time the manager found out, Peter, with his fluent English, hard work and native intelligence had learned enough that it made sense to continue to employ him.

Peter Savarino

Peter's Uncle Sam and Aunt Lucy Savarino, childless themselves, discovered Peter's younger brothers were in an orphanage and took steps to adopt them. With the boys in good hands, Peter moved to Hillsdale where he got a job at the Alamo Manufacturing Company, continuing to be employed by the successive businesses that bought the Alamo building. He rose quickly to become a supervisor over the older Italian men, who were still struggling with English. A self-taught musician, Peter also played in a band in Hillsdale and on a riverboat on the Ohio River.

When a severe allergy to the oil used in tool and die manufacture required a new line of work, in 1940 Peter established the Hillsdale Merchandise Company, which sold furniture. It was lodged in a building that stood to the northeast of the Savarino home on E. St. Joe Street. Pianos were part of the inventory, which turned out to be an inspired choice. Peter's son, Joe, was a gifted pianist who studied for a while at Julliard. The summer Joe was 10 he showed his versatility by playing popular music with the Rhythm Masters five nights a week at Devil's Lake. Anyone showing an interest in buying a piano from Peter was treated to a serenade by Joe, which convinced them that they, too, could make beautiful music if they just bought a piano from the Hillsdale Merchandise Company. Soon gum and candy were added for the benefit of people who used the store as a social gathering place. Dairy products and then a party store followed. Peter followed the new direction his business had taken, and furniture became a thing of the past.

Joey Savarino, age 10, playing at the Devil's Lake Pavilion

With 300-500 men working at Hillsdale Steel Products across the street from the Savarino business, it made sense for Peter to add liquor to his stock. This necessitated moving the door to his establishment from South Street to E. St. Joe Street to comply with a law that dictated the required distance of liquor sales from the location of a church (Trinity Lutheran, in this case). From there it was a short step for Peter to expand his party store into a grocery and then to add a snack bar for the men to hang out in while their wives shopped. With the urging of Peter's son, John, and the cook, Harry Ginolfi, the snack bar became Savarino's Restaurant in 1965. In the process, the Savarino home was moved down Griswold Street across from Waterworks Drive.

Most of the Italian families who came to Hillsdale pursued the American dream with hard work, a refusal to fail and an unshakable belief that they would succeed … which they did in greater measure than anyone could have predicted.

JoAnne P. Miller and Connie Cooper Eltman

2014